Session 1

On the verge of opening the zoom link to our first session of the AFYN programme, it did not matter that I had worked with teenagers in workshops numerous times before. The digital medium felt alien, the atmosphere in the session more resolutely stilted: I was nervous.

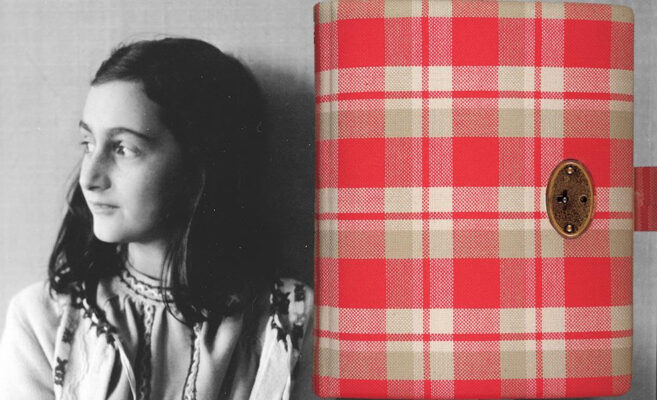

ccccThe coordinating teacher from Shiv Nadar School, Kirti Kaul had shared a link to the digital exhibition with the students, following our introductory session the previous week where Aaron and Morgan took us on a virtual tour of the Anne Frank House. Not wanting to bore my audience with a long-drawn virtual tour of the entire exhibition, especially when we were meeting for the first time, I had accordingly prepared a narrative, highlighting specific issues in the panels I wanted to bring to the students’ attention.

ccccMy careful planning however went askew on learning the students had almost no familiarity with the content of the panels except for very sketchy ideas of Anne and her context. Changing tracks, I decided to pick themes I wanted to address in some detail from the first eleven panels only, keeping time constraints in mind. And so my interactive ‘tour’ addressed in some detail the following topics: the cultural background of Anne’s family (and the multiple features of their identities); reasons for discontent in Germany (plus a brief recap of the Treaty of Versailles,etc.); Hitler’s growing power and popularity, effective use of media for propaganda—photography perspectives, cheaply available radios; the NSDAP’s programmes for involving children in the larger Nazi project; Under what circumstances does a public book burning take place? Attitudes towards difference; Communities targeted—idea of racial purity; Eugenics; origins of the construct of race; the Nuremberg race laws.

-Ranita

Session 2

We began this session with picking up from one of the key points that was made in the previous one—what is race and how it was narrativized under Hitler’s occupation. Here, we discussed the notion of ‘German blood’ and how those who fell outside this category were treated as not being a full citizen of Germany. In this then, what does Hitler do to make the majority if not all Germans believe that Jews were a threat to the Germans, thus introducing them to the term propaganda that is to keep telling a lie to a point where it becomes believable to the people.

ccccEmerging form that, we tried to answer the question—what is the first step to discrimination? To which we discussed that it is the experience of isolation and alienation that are the building blocks on which discrimination is built. Here we drew from some instances illustrated in the exhibition panels.

ccccThe second part of the session drew from Resource 9–Past and Present: Anne Frank and discrimination. Each student was given a quote which they were to read and reflect upon with a focus on understanding the different circumstances of discrimination in the case of Anne Frank. We followed this up with a discussion drawing from their thoughts on those quotes. This conversation was geared towards bringing out the larger concept of systematic discrimination—how discrimination takes roots and how it then progressively tightens its grip over all facets of people’s lives before they can notice it. Therefore, discrimination is neither built nor broken in a day, it is built over a period of time. Linking this to the present context closer home, we brought in the example of the caste system and untouchability in the Indian context and how that has proceeded and continues to sustain its hold radically on people’s minds.

ccccIn the final segment of the session, the students were given the activity in Resource 10–Timeline of the persecution of the Jews in the Netherlands which traces the trajectory of the discriminatory laws that were passed under the Nazi regime and the implication that had on the lives of ordinary people. This began with the students sharing what a day in their life looks like. We then proceeded to thinking how those discriminatory laws under the Nazi regime would impact people’s everyday lives to get a sense of the extremity of the restrictions and consequently the confined existence that people including children like them were subjected to.

– Rajosmita

Session 3

After a quick icebreaker, I screened a segment of the Anne Frank House Discrimination Explainer video (from 0:47 – 3:12) Continuing the topic of exclusion from the previous session, some of the points we discussed after the screening included: citizens’ rights, access to public space, different aspects of government surveillance, exclusion as persecution.

ccccIn light of this, I shared specific images from Resource 8 of the toolkit that students in turn read out the captions of (Resource 8: Pg 1 – Image 4, Pg 4 – 1935, 1938, Pg 6 – 1941 and Pg 8 – 1944). The discussion involved encouraging the students to identify what grounds targeted community members were being persecuted on the basis of, and to reflect on what individual rights mean in such scenarios. I also invited the students to share anything from their own lives/observations or contemporary times that were invoked by any of the images that were shared. One of the points that came up in relation to an image showing the public humiliation and persecution of an ‘inter-faith’ (Jewish and Christian) couple, was the anti- ‘forced’ conversion Acts, recently passed in a few Indian states including UP, also being called the anti- ‘love jihad’ laws. I had previously shared a news-clipping on the same with the students as part of a home assignment.

ccccNext I screened an episode from Anne Frank’s Video Diary (0:44 to 3:46 of ‘ Hatred of the Jews’) which we subsequently discussed. The structural workings of the Nazi project as shown in the previous video were driven closer home.

-Ranita

Session 4

The primary objective in this fourth session was to explore the concept of Identity. Following a quick energiser, we started with a quick recap of the film clip from Juice that was screened in the previous session and a discussion leading out of that into answering what the students understand of the term identity.

ccccIn the next segment of the session, we screened and discussed the Anne Frank video diary—Who are you? We began with drawing up a list of all the many different markers that went into describing Anne, thus also showing it to be a vast and dynamic concept. One of the key points that came out of watching that clip was the fact that there were two Annes—one that people knew and the other side of her including her profoundly thoughtful nature that people including her father didn’t know existed. Therefore leading to the question—why is it that we as people choose to not share certain shades of our identity with others. To this the students responded by giving instances from their lives when this has happened, where the fear of judgement was the main reason that stopped them from speaking their mind or being themselves before others. They were to then draw up a list of the elements that go into making their identity which included gender, religion, class, caste, nationality, occupation, interests. This was followed by a conversation around the following questions—Is every element of our identity always a conscious choice? How is our identity influenced by what others think about us? Is identity fluid? Should I get to say what is right/ wrong about your identity?

ccccWe then did the ‘Tell me who I am’ activity where the students were supposed to guess some elements that go into the making of the facilitator’s identity. This activity was geared towards realising that we as people must be aware of the prejudices we hold in making hasty judgements about people, that is usually rooted in our socialisation leading to our preconceived notions about their identity. This then influences the way we interact with them often leading to differential and discriminatory treatment. Linking this idea to the context closer home in recent times, the students came up with examples of how the people belonging to the lowest castes are confined only to some of the lowest occupations in the caste hierarchy including the manual scavenging and cleaning carcasses. The other example that came up were the gendered games that children are expected to play through their formative years given the biases that people hold about the games that a girl would enjoy playing versus those a boy would enjoy.

ccccWe then tied this into some of the images of recent protests happening in the country, prompting them to think about the linkages between protest and identity. What brings people together in these circumstances? Do only like minded people protest? In that case, why is it that those who are not affected directly also gather at these protests?

ccccIn the final segment of this session, the students were given the activity ‘Let Me be Myself’ with the central idea of understanding that identity is deeply embedded in the context that we exist in. This then leads into the question around diversity which we would pick in the next session. Given that we could not complete the last activity in this session, we carried it on to the next one.

-Rajosmita

Session 5

Themes: Identity and agency

We began with a fun improvisatory relay story-building activity ‘I can’t remember what happened next’ to jolt us into thinking on our feet.

We had previously shared Resource 132 (‘Let me be myself’) with the students as an assignment. In this session we built a discussion around their responses, focusing on: what features of their identity they think are permanent and what they think are not, what kind of situations/environments/company brings out what aspect of their identity. The conversations grew animated with many differences of opinion among students—one student remarked that most features of identity could changeover time.

Acting on this cue, Rajosmita, co-facilitator for this session, did a re-cap of the previous session which had been on identity, for the students who had missed it. The trajectory of this interaction allowed me to organically present the question: Are our actions our identity?

Here, I offered them a snippet of Holocaust Studies history: the overwhelming need to understand how a programme such as the Holocaust could be implemented, a little about Raul Hilberg and the origins of the categories of perpetrator, victim, bystander and (later contribution from Jan Gross) helper.

This session concluded with an extended discussion on the above categories, their fluidity, the agency of those occupying the position of any of the categories, using 1) a collation of quotations by victims/survivors, helpers and perpetrators in the context of the Nazi-conducted Holocaust and 2) a clip of the trial scene from the film The Reader (beginning to 3:00).

-Ranita

Session 6

In this session, we began with a quick recap of some of the key issues discussed in the previous session, primarily that identity is deeply embedded in the context and the circumstances in which we exist, therefore to realise that identity is fluid.

ccccWe then spoke about the diverse facets that go into making us who we are—gender, religion, caste, class, nationality, language and how circumstances influence some markers to gain prominence over others in specific moments. For example when applying for a country specific scholarship at University, our nationality takes centre stage before we can go on to tell our own story. The question that we then put forth is—what is diversity? We unpacked diversity in the following steps:

- To acknowledge difference—that we assume different identities

- The need to navigate through those differences meaningfully

- To reject homogeneity that is to say that we are not the same in the identities we assume, we do not believe, nor do we say or stand for the exact same thing. Therefore also rejecting generalisations about an entire people. However, to emphasise the critical need to respect these differences in this.

- Finally, to make sure that these differences in identities cannot and should not lead to differential treatment that is discriminatory.

ccccThe next question that we addressed was why it is becoming increasingly difficult to grapple with diversity despite living in a globalised world today. We began with asking them about instances of intolerance from around the world at present. In discussing this then, we said that while globalisation has majorly opened up the world to the extent that we are so connected that we call this a global village, there has been a counterforce from the powerholders of nations to contradict this opening up and accessibility. This has come in the form of constant calls of making borders tighter, communities closed off allowing for only one kind of opinion to thrive while delegitimizing all others and therefore the push towards restricting who occupies what space.

ccccWe followed this with a little activity where they were to think about instances of differential treatment meted out to people who assume different identities from them in their day to day lives. We got quite a diverse range of thoughts to this question.

ccccThe next activity was to pick quotes from Resource 9 [quotes where Anne discusses her anxieties of being discriminated against due to her identity as a Jew] and get the students to respond to them. This was directed towards thinking about how diversity is systematically attacked under an authoritarian regime. Drawing form this, some of the key points that were discussed were as follows:

- The complexities of grappling with a concept like diversity in practicality.

- The question of representation in this context—who speaks for who and whose voice remains unheard.

- Equity versus equality—the need for affirmative action to address the entrenched disparities in society because equality is not enough

when the starting point for so many people are so disadvantaged which then implies that we would have an unfair advantage simply because of our place in society. Some students brought up the example of caste reservation in the Indian context and their thoughts on that which we then discussed and unpacked through this larger concept. Therefore the need for equity over just equality if we have to be truly diverse and value that diversity.

ccccIn the last segment of this session, the students did the activity from Resource 20 on Diversity. The discussion here was centred around the question—’Do you think we often reject people and their opinions because of the first impression we have of them?’ Thus thinking about how our prejudices about other people become hindrances in our ability to acknowledge and appreciate difference.

-Rajosmita

Session 7

Continuing from the last session’s activity on Diversity, we began this one with a small exercise: write in three phrases what ‘your culture’ is. Here students shared widely different aspects from the festivals they celebrate, the things that they like doing most, the ideas that they strongly believe in. So we built a conversation around these diverse markers that go into building one’s culture.

ccccFrom here, we returned to the categories of Victim, Perpetrator, Helper and Bystander —a subject we had addressed in Session 5. I asked the students to share with me an incident they considered unjust. Using that as an example, we discussed how the roles played by even the same set of people transformed depending on the situation of injustice. I then assigned each student one of 3 situation cards (devised on the basis of Resource 15) and gave them 6 minutes to think and type in their responses. Each situation card had 2 respondents which allowed us to get into an in-depth discussion on why the students responded as they did, and how their approaches to the different roles (perpetrator and victim mostly) changed from one situation to the next.

ccccFollowing this I did a brief segment on fascism and culture, sharing with students images of what the NSDAP considered ‘entartete kunst’. Talking about what art was considered ‘degenerate’ and what ‘German’, the discussion was woven around the questions: i) Why did a fascist government need to go to such lengths to shape ‘culture’ to its agenda when it was already in power? ii) Can art be dangerous and why? This invited a range of interesting responses from the students. One of them said that art was indeed dangerous because it is at its heart, expression, and any expression that can reach others and that is opposed to the ideals of the ruling power can therefore be seen as a threat. Another student opined that the Nazi government needed to mould culture to its convenience in order to shape people’s thinking and limit critical questioning.

ccccIn this segment, we tied this conversation to the relevance of culture in driving and influencing the socio-political atmosphere in the country at present in specific ways. Here the example Rajosmita shared with them was that of the very well renowned Carnatic music vocalist TM Krishna, who has extensively used his music in making socio-political interventions in the present landscape and establishing a dialogue against discriminatory systems including the caste system in India. His most recent book—Sebastian and Sons is an in depth study of the lives of the people who make the mridangam which is one of the key instruments in Carnatic music. However the making of that instrument requires working with animal skin and is done by the Dalit communities. It chronicles the lives of these makers because nobody wants to confront these harsh realities. The launch of this book was called off at the last moment by a prestigious organisation with the argument that the book creates discomfort among the upper caste people in the narratives that it brings out. Therefore, the question we addressed here was—how is culture critical in constructing narratives and what happens when those narratives challenge the ways of the powerholders? What happens when the voices of the marginalised bring out the harshest realities?

ccccWe closed this session with an exercise for the students to bring back for the next and last session of the programme. The exercise consists of a small questionnaire exploring the students’ responses (and the motivations guiding them) to a situation of injustice they identify from their own lives.

-Ranita

Session 8

Today, our last session of this pilot for the Anne Frank Youth Network programme, we began with a ‘story’-building game we had played before, but this time on the theme of ‘Anne Frank’. After three rounds of sentences on Anne’s life, I asked the students to shift focus to the realm of society for the fourth and final round. What was intended as an ‘icebreaker’, took an interesting turn when I questioned a student’s uncritical usage of the phrase ‘Aryan race’ to refer to NSDAP members and proponents, leading to a brief conversation on the importance of naming.

ccccWe had ended the previous session with a brief assignment for the students. Since the students had for various reasons not come back with it, we did the assignment in the session. They were given 8 minutes to formulate responses to:

- Share/write down one act of injustice that you have witnessed/regularly witness around you.

- Would you respond to it?

- If yes, how would you respond to it?

- If no, why would you choose to not respond?

ccccTheir answers ranged from discrimination in the classroom on the basis of skin disease and complexion, ‘disability’, to gender-based discrimination in sports and class-based prejudices in domestic labour. We discussed their responses to the situations they shared and explored how effective such responses can be in highlighting discrimination, alternative ways of responding, and more broadly, ways in which to counter discrimination through cultivating meaningful, deep-rooted sensitivity.

ccccNext I asked the students to take a further step outwards from their personal lives and pick an instance of injustice and/or discrimination from northern India (since they live in and around Delhi). They had 10 minutes to use the web/media to come up with their selections. Some of the instances picked were: the anti-CAA protests and the 2020 Delhi riots, skin colour discrimination and fairness creams, hostility towards Bihari migrants (the student confided that she herself had been guilty of this before) and people from North Eastern states in Delhi, including mocking different features of their culture. One student typed in ‘Rowlatt Act’, specifying that her example was from ‘history’. This gave us a chance to have an expansive yet personal discussion, addressing topics including mainstream media’s role in how riots are narrativized, and ways in which colonial legislations have continued into independent India’s laws.

ccccReturning to the students’ responses to the first assignment, I asked them to think of ways in which they would amplify their response to the instance of discrimination they had shared. Petitions, writing well-researched articles and door-to-door campaigning were offered as answers. We briefly talked about how different combinations of these strategies could be utilized. The students committed to get in touch with us if they took up a campaign against any instance of discrimination they encountered/recognized. The session concluded with my recommending three films to them that may offer food for thought: Look Who’s Back, Jojo Rabbit and closer home in the context of Delhi, Axone.

-Ranita

~