What does the word border mean? When do we think about it? When politicians talk about them? When wars are fought?

Does it require an event to initiate a discussion about borders?

Exchange for Change, a yearlong program conducted in collaboration with the Citizens Archive of Pakistan addressed, through intensive workshops, the idea of borders. Among other things. This project takes a critical look at common perceptions, or rather, misconceptions that we harbour about our neighbours on the other side of the border. Misconceptions that are perpetuated by the fact that there never is any real, tangible interaction between people in India and Pakistan. The fact that opinions are based on misguided politics and what the media chooses to represent.

Exchange for Change builds a dialogue between a very neglected (when it comes to bilateral relations) demographic- school students in India and Pakistan.

A one of its kind Track 2 diplomacy project, Exchange for Change reached out to 600 students from middle and high school in Calcutta, India and an equal number in Karachi, Pakistan. The project was divided into four phases: the Letter series, the Photography series, the Oral History series and the Video series, each phase spaced out over a few months.

Swaleha Shahzada, the Executive Director of the Citizens Archive of Pakistan kicked off the first phase with orientation workshops in each of the participating schools, which included Abhinav Bharati High School, Chowringhee High School, La Martiniere for Boys, Lakshmipat Singhania Academy, Modern High School for Girls and Saifee Hall.

This in itself acted as a great start to the project. The curiosity in the children’s voices when asking Swaleha about life in Pakistan and the wonder when she told them how very similar lifestyles in India and Pakistan were seemed to bring to light our instinct to forget about the countries’ shared pasts (of course we would have similar lifestyles) and concentrate on opinions made by others.

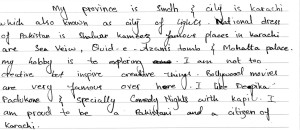

Students in Calcutta wrote letters describing their lifestyles and interests, with questions for their friends in Karachi. These questions were answered, descriptions of life in Pakistan were given and counter questions about India were asked in the replies to the letters.

A few letters that were exchanged contained a deep-rooted sense of anger towards the ‘other’. Coming from 13 year olds we did find this alarming. But this also reiterated for us the need of a project of this nature. On both sides of the border these sensitive letters were used to conduct in depth interactions and discussions with all the participants of the project. However we decided to give the responsibility of replying to these only to the older students in the group. The students who were given the letters took their time over them, mulling over the sentiments and the question of mindsets. They discussed it amongst themselves, working out the best way to reply to these letters. The anger was acknowledged and so were the possible reasons behind it. They concluded that the best way was not to get angry in turn but to respond rationally and hope that it would initiate a thought process in the reader—one that could change the mindset.

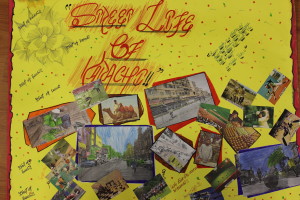

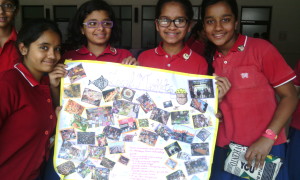

The new ‘pen-pals’ then went on to exchange post cards and charts, which depicted their neighbourhood, their customs and traditions, food habits, festivals and other cultural facts in great detail.

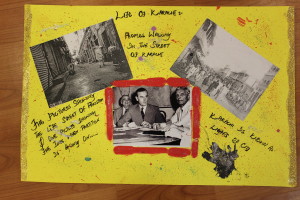

This was followed by exchange of oral history interviews from both sides of the border. This was the most engaging and interesting part of the project for most of the students. They had to first locate elders within their communities who had experienced the partition and were actually displaced at the time. They then formulated questions for the interviews with the help of their teachers. Some students realised through this exercise that there were stories within their families that they were not aware of and yet others encountered elders that were not very willing to talk about their memories of the time. A common thread in most of the interviews was accounts of how life has changed over the years. The sharing of these oral histories across the border truly emphasised the fact that there really is no ‘other’—that we share not only common cultural practices but also a shared past that is made up of joys and sorrow.

Each phase involved discussions with the children before and after the activity was conducted. While there was a constant sense of marvel at being a part of such a project, there were also notes of dissatisfaction.

Would such a project actually work? Was there any real use?

While these comments were few and far between, it gives one pause. The need to reflect. What was very interesting was a discussion at La Martiniere School for Boys. One of the participants asked a similar question. About whether such a program would be useful or not. This lead to a conversation between him and his classmates—many believed in the merits of this kind of diplomacy. Through the course of the discussion, which happened without any intervention from the teachers and the program facilitator, the students agreed to give the project a chance.

Discussion about the project at La Martiniere for Boys

Working with 600 young people from India and another 600, albeit long distance, from across the border is not easy. Mindsets came to the forefront. ‘Hand me down’ experiences, particularly in the case of incidents of violence, became ones own experience. Emotions played an important role. But what was exciting was to see the change. Sometimes immediate, sometimes grudgingly. But a change nevertheless. Who we have been traditionally conditioned to consider as ‘the other’ is actually someone just like us. With similar interests, similar dislikes, similar joys, similar sorrows.

-Paroma Sengupta