The first talk as a part of the History for Peace project was titled ‘A missing General, a trusted jeep, and submerged narratives of 1971’. A title like that is enough to pique ones curiosity!

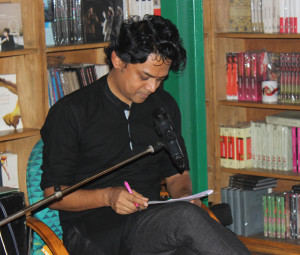

Naeem Mohaiemen, who was the speaker for the evening, is a historian and visual artist working in Dhaka and New York. He uses film, photography, mixed media sculptures, and essays to research borders, wars, and belonging within Bangladesh’s two postcolonial markers (1947 and 1971). In addition to his work as a visual artist, Naeem is a Ph.D. student in Historical Anthropology at Columbia University, and a 2014-2015 Guggenheim Fellow (film).

Naeem began the talk by using photo and media evidence to set the context about relations between the three countries in the subcontinent. The trailer from the film ‘Gunday’ was one of the examples used to show how the turmoil of the 1970s is represented in mass media.

An example used to illustrate the difference in perceptions was the popular Pepsi ‘Mauka Mauka’ advertisement from the last cricket World Cup match. The one showing India and Bangladesh showed India as the ‘creator’ of Bangladesh and the submissiveness of the Bangladeshi side in the video immediately created ‘response’ videos from across the border. The events of 1971 were also dealt with in different ways in terms of its representation in the political arena by the various Governments. In fact, they are now seen as a branding opportunity (and a very productive one at that), for example, a photo (manipulated using Photoshop) of the ‘Mukti Bahini’ freedom fighters used in an advertisement for a bank.

(Photo by Debleena Sen. On screen: Photo of 2013 protest outside Pakistan Embassy, Dhaka, by Atish Saha.)

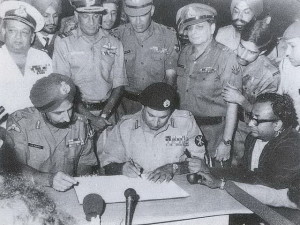

Moving onto the photograph in question—an iconic one of the surrender ceremony of December 16 1971, Naeem spoke of the glaring incongruity in the photograph. Representatives from the Indian side and the Pakistani side, Lt General Arora and Lt General Niazi, respectively, are prominently in the frame. The missing man is the Bangladeshi representative—General Osmani. His absence is often glossed over, because of, as Naeem says ‘a quiet embarrassment about incongruities’. Reasons for his absence, such as the failure of his jeep seem dubious and unconvincing. Key players from the incidents of 1971 from the Bangladeshi side were not invited to the surrender ceremony.

The use of photographs such as these as evidence of facts needs to be questioned, and the discrepancies need to be brought to light, discussed and analysed. Who takes a particular photograph, the political (or otherwise inclinations) of that person, who is in the photograph and who authorizes the use of a photograph (or video) are all questions that need consideration. Naeem talked at length about the ‘submerged narratives’ that exist in these images that have the potential to ‘construct’ history. On the other hand in this day and age, digital manipulation of photographs is almost a part of our daily lives, leading us back to the question of the use of photographs as evidence of facts.

This brings one to the question of whose history, or rather whose version of history is correct. As Naeem says in his book ‘Prisoners of Shothik Itihash’ (Prisoners of a Correct History) ‘…I wondered who was going to decide for us, once again, what was and was not “correct history”…’

The use of visuals is still a very important pedagogical tool. One member of the audience said ‘ I wish more of us teachers would use photographs to teach analysis and critical thinking.’

The interaction with the audience was an equally interesting one, with questions ranging from the importance of photojournalism, to whether Naeem was planning to make a film based on all his research.

It was a stimulating start to the History for Peace project, and we hope that this is the beginning of many more such evenings. Food for thought, ideas for educators, the sharing of initiatives and experiences.

–Paroma Sengupta