Day One: Of Looking Inside, Looking Outside and Transcending Limits

A dark room with different images being projected on two walls. A silent flow of images. Bodies of riot victims being shovelled off a truck, posters of feminism, iconic photographs, a new-born girl child being killed by her father, two men kissing among much merriment . . . And Philip Glass played in the background. The participants came and sat in a circle in this room while we welcomed them to the workshop. They were then taken into another room where we played a series of clips—very intense, very violent, very jarring. Each participant was invited to stand in front of a mirror and watch the film being projected on his/her body while the others looked at this slightly distorted flow of images taking note of the changes in the participant’s body language.

Then we read together—about art, community, conflict and the possibility of peace. We read Tzvetan Todorov and Ryan Lobo. We discussed many frivolous and serious quotes about art and life written by painters, sculptors, writers and philosophers. Each participant was asked to discuss one quote. It is wonderful how some of these remained with us even at the end of the workshop. Like ‘every man is an artist’ or ‘good art is not what it looks like, but what it does to us.’ Another one often came up: ‘You see things; and you ask, “Why?” But I dream things that never were, and ask, “Why not?” ’

We thought: it is only a matter of fate, chance, accident that we happen to be safe, leading indifferent lives. Yet there is conflict if we disturb the numb surface of things. We spoke about ‘the banality of evil’. We then asked: Who am I? How do I picture myself? What is my sound—my vibration? What does my soul look like?

The next exercise attempted to translate these ideas into visuals. Participants were asked to gather around a large sheet of paper and depict themselves. In whatever manner.

A young boy painted himself as a werewolf. Another made disconnected sketches of a butterfly, a lion and a flower. One of them played with the idea of a thumb print as identity. A girl saw herself as a broken chain.

We walked away from the painting and we now tried to see it in its totality . . . concentrating no more on our little corners of the whole. Reflecting on this totality for a while we thought of this as an exercise in transcending the self to visualize a larger community. Each of us thought of three words that best describe the image of the whole. We wrote them on chits of paper and mixed them up. One of us picked up one word. It turned out to be ‘Life’.

So there we had a name for this community of artists. After all, what is a community without a name?

Day Two: Picturing the Other . . . on the Self

We began by talking about abstract depictions . . . thinking of ways to speak the unspeakable. We saw images.

It is often wiser, one is told, to pick one’s battle. We thought of one subject—one issue we would like to speak for. And then, without speaking, through a game of Pictionary or Dumb Charades, we tried to communicate this issue to the rest of the group. Amita wanted to talk about the problem of elitism in terms of dissemination of higher education. Rahul sketched freedom embodied as a bird being shot down.

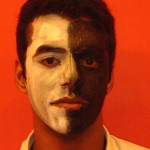

For the second activity of the day, we tried to narrow down our concern. From a problem to an individual. Another subject—it could be a man, a woman or a dog. Often the most identifiable picture of oneself is one’s body, one’s face, that which stares back from a mirror. So then we began to conceive that ‘Other’—we thought of the appearance, the feel, the mood. And then we tried to paint that subject on the canvas of the most tangible selfhood—the body.

Ayush wanted to paint a victim of racism on his face. Amita conceived of a victim of domestic violence. Utsarjana thought of a subject who cannot speak but will not ‘keep shut’.

Day Three: Of Dystopia and Utopia, Of the Possible and the Impossible

The day began with an impromptu, heated debate on the subject of Democracy. While Sagnik defended the model of benevolent despotism, Kathakali condemned the infantilization of the masses. We asked if it is right to think of the masses as stupid? How far is political representation possible and effective? We were left wondering about the limitations of the models of governance we have today. Is there a way out?

The activities of the day began by looking at images of heaven and hell, the this-worldly and the other-worldly. Also, works of artists who painted a grand sweeping vision of the totality of the human condition. However biblical, however white, however partial—one cannot take away its raw force, the courage of the idea.

Hell, fire and brimstone, dystopia, the breaking point of despair—these are easier to understand than heaven. We began by trying to picture hell, because we are all closer to it. We have seen it, here and there, in holocausts all over the world. We made collages using old newspapers and magazines to create the image of a hellish reality that we see all around us through media images of death and despair.

Urooz asked, ‘Is there a way out?’

Herbert Mercuse once lamented that the worst sign of our time is that there is no way to conceive of a route, a possible way from here to utopia.

The last activity of the workshop was to concentrate on the idea of utopia. Is it possible to paint the impossible? The idea was to push the limits of representation, to see if we can speak the unspeakable.

We discussed the concept for a while, taking turns to share our idea of perfection with others. And then we agreed on a vision.

We thought of a bare, blurry human form—an inhabitant of utopia. And we imagined the freedom that this human being embodies: not limited by caste, race, gender, sexuality, class and other identities; not limited by ideologies and indifferences; not limited by anger and hate.

We shook hands as a community called ‘Life’, having dreamt of a possible impossible utopia.

— Moumita Sen, workshop facilitator.